Myanmar coup: Democracy stares into the abyss

A military coup that overturns a landslide victory for Suu Kyi could reignite one of the longest civil conflicts in the world

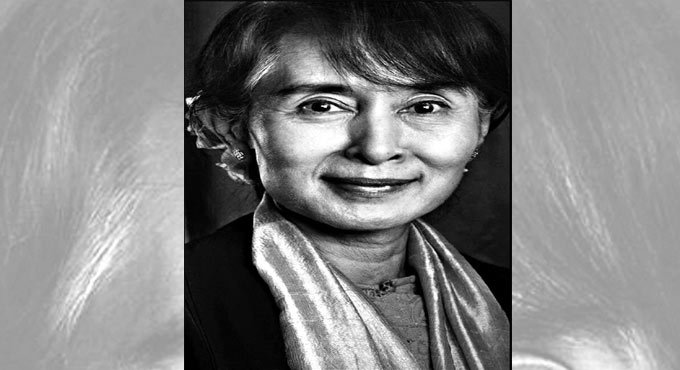

The future of the fragile peace process that sought to end Myanmar’s decades-long conflict between the military, armed ethnic groups and militias became even more uncertain after the military coup on February 1, which was supposed to be the first day of a new session of Parliament following November elections that Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won in a landslide.

The military announced that it will take power for one year, accusing Suu Kyi’s government of not investigating allegations of voter fraud in recent elections, in which the military-backed party fared poorly. The Election Commission has refuted the allegations.

Long Civil Conflict

Over 20 ethnic groups have been fighting the military over control of predominantly ethnic-minority borderland areas, including Shan, Kachin, Karen and Rakhine states. The groups have sought greater autonomy for their natural resource rich regions.

Myanmar has one of the longest civil conflicts in world, with fighting continuing at different times across the country since 1949. Many of the armed groups want greater autonomy, which they feel was promised by Suu Kyi’s father, Gen Aung San, via the Panglong Agreement of 1947. Aung San was assassinated in 1947. Decades of junta rule that followed resulted in a slew of human rights violations, including the use of civilians as slave labour, rapes, extrajudicial killings and burning of villages.

“When the Myanmar military was coming, ethnic Shan, Kachin, Mon, Karen and others would run into the jungle,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. “Atrocities against ethnic people by the military were widespread, systematic and done with impunity.”

When democratic reforms began in 2011, unilateral ceasefire agreements were signed by several groups. In 2015, a nationwide National Ceasefire Agreement was formed. Further hope for the peace process came when Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party swept to power with a landslide victory in the 2015 general election. In same year, the new government helped organise a “Union Peace Conference — 21st Century Panglong,” making further inroads for peace. Yet even with ceasefires and peace summits, fighting has continued across the country.

In 2018, a UN fact-finding mission released a report on Myanmar describing massive violations by the military, also called the Tatmadaw, in three ethnic states. “During their operations, the Tatmadaw has systematically targeted civilians, including women and children, committed sexual violence, voiced and promoted exclusionary and discriminatory rhetoric against minorities, and established a climate of impunity for its soldiers,” said Marzuki Darusman, the mission’s chairperson.

The military also targeted minority Rohingya Muslims in a brutal 2017 counterinsurgency campaign that drove more than 700,000 from Rakhine state to neighbouring Bangladesh. Critics say the army’s actions constituted genocide. The Rohingya have not been involved in the peace process.

Suu Kyi’s Renewed Effort

After her party won the general election last November, Suu Kyi spoke of a renewed effort in the peace process, with the hope of including political parties and community organisations. But the military’s takeover could drastically shift chances for the peace process.

Several armed groups have released statements condemning the coup. “Due to the seizures of power, the National Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) and the peace process which are being implemented by the participation of the government, the Parliament, the Tatmadaw, the political parties and the ethnic armed organisations can cease to work,” said a statement by the Restoration Council of Shan State, a large ethnic army headquartered on the Thai-Myanmar border.

The Karen National Union, one of Myanmar’s oldest armed ethnic organisations with considerable influence over other NCA signatories, called for the release of all arrested leaders and for political issues to be resolved peacefully. But some notable groups have not commented, including the Northern Alliance, consisting of four armed organisations that have been involved in some of the most violent clashes in recent years.

“It’s going to be particularly important to see where the other groups stand,” said Laetitia van den Assum, a member of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State created by the government and the Kofi Annan Foundation.

Min Aung Hlaing

The man installed by the army as Myanmar’s president after the military coup is best known for his role in the crackdown on 2007 pro-democracy protests and for his ties to still powerful military leaders. Myint Swe was the army-appointed vice-president when he was named on Feb 1 to take over after the military arrested Suu Kyi. Immediately after he was named president, Myint Swe handed power to the country’s top military commander, Senior Gen Min Aung Hlaing.

Under Myanmar’s 2008 constitution, in cases of national emergency, the president can hand power to the military commander in chief. That is one of many ways the military is assured of keeping ultimate control of the country. Min Aung Hliang, 64, has been commander of the armed forces since 2011 and is due to retire soon. That would clear the way for him to take a civilian leadership role if the junta holds elections in a year’s time as promised.

The military justified the coup by saying the government failed to address claims of election fraud. “It seems there’s been the realisation that Min Aung Hlaing’s retirement is coming and he is expected to move into a senior role,” said Gerard McCarthy, a postdoctoral fellow at the Asia Research Institute.

In 2019, the US government put Min Aung Hlaing on a blacklist on grounds of engaging in “serious human rights abuse” for leading army troops in Myanmar’s northwestern Rakhine region. In the same year, the US Treasury Department froze Min Aung Hliang’s US-based assets and banned doing business with him. Earlier, it banned him from visiting the United States. Min Aung Hlaing also was among more than a dozen Myanmar officials removed from Facebook in 2018. His Twitter account too was closed.

Myint Swe’s Power Play

Myint Swe, 69, is a close ally of former junta leader Than Shwe, who stepped down to allow the transition to a quasi-civilian government beginning in 2011. That eventually allowed Myanmar to escape the international sanctions that had isolated the regime for years, hindering foreign investment. It also enabled Myanmar’s leaders to counterbalance Chinese influence with support of other governments. But with the coup, Beijing may well end up with still more sway.

Myint Swe is a former chief minister of Yangon, Myanmar’s biggest city, and for years headed its regional military command. During the 2007 monk-led popular protests known internationally as the Saffron Revolution, he took charge of restoring order in Yangon after weeks of unrest in a crackdown that killed dozens of people. Hundreds were arrested. In 2017, Myint Swe led an investigation that denied human rights allegations in Rakhine, saying the military acted “lawfully.”

Tricky China Ties

Even if China played no role at all in ousting Suu Kyi, Beijing is likely to gain still greater sway over the country. That’s especially likely if the US and other Western governments impose sanctions to try to punish the regime.

Beijing’s initial reaction to the coup was measured. But China has invested billions of dollars in Myanmar mines, oil and gas pipelines and is its biggest trading partner. But while China’s ruling Communist Party tends to favour fellow authoritarian regimes, it has had a fractious history with Myanmar’s military, sometimes related to its campaigns against ethnic Chinese minority groups and the drug trade along their long, mountainous border.

It was partly a backlash against China’s growing dominance of Myanmar’s economy a decade ago that led the previous junta to shift toward democratic reforms that enabled Suu Kyi to join Parliament and become the nation’s de facto leader.

Suu Kyi has shifted closer to Beijing in the past few years as she defended the military against condemnation of atrocities against Rohingya. That may have deepened military leaders’ distrust. “It was always a risk that the military would step in to try and shore up their power,” said Champa Patel, director of the Asia-Pacific Program, Chatham House. “Their insecurity has deepened as (Suu Kyi) consolidated her power within the country and deepened ties with countries such as China.”

The coup came just three weeks after a visit by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, who met with Suu Kyi. The visit was seen in part as an endorsement of the victory of Suu Kyi’s party in the November election. Some have speculated that Beijing might have given a covert nod to the generals.

Regardless of what internal politics, antagonisms and personal ambitions might have driven Min Aung Hliang and other military leaders to seize power, China is bound to continue to expand its influence in Myanmar given the huge projects already under construction and the depth of Chinese involvement in businesses ranging from casinos, factories and property development to pipelines and ports.

China has massive commitments to projects in mining, hydropower and other construction, part of the $21.5 billion it has pledged in investment in Myanmar. Suu Kyi’s government had been slowly moving ahead on such projects, some of which face strong local opposition. (Agencies)

Dramatic Fall

Dramatic Fall

After taking the helm of Myanmar’s nascent pro-democracy movement in 1988, Suu Kyi’s brave defiance of military rule, at high personal cost, made her the object of worldwide adulation. She won the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize, cited for being “one of the most extraordinary examples of civil courage in Asia in recent decades.”

When her nonviolent struggle finally paid off in 2015 with a smashing election victory by her National League for Democracy party, there was optimism that Myanmar had finally turned a corner after decades of military rule.

Then came the crackdown. In 2017, Myanmar security forces launched a counterinsurgency operation in western Rakhine state that, compelling evidence shows, involved mass rape, killings of Rohingya and the burning of entire villages.

As the magnitude of the Rohingya tragedy emerged, Nobel Peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu felt compelled to appeal to Suu Kyi. “My dear sister: If the political price of your ascension to the highest office in Myanmar is your silence, the price is surely too steep,” the South African wrote in an open letter. “We pray for you to speak out for justice, human rights and the unity of your people. We pray for you to intervene.”

The European Parliament suspended Suu Kyi from the group of former winners of Sakharov Prize, its top human rights prize because of her “failure to act and her acceptance” of the oppression of the Rohingya Muslims. Canada too stripped Suu Kyi of her honorary citizenship.

But Suu Kyi has defended the military action against the Rohingya and pointed to a lack of understanding of the complexities.

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .

Related News

-

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

7 hours ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

8 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

8 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

8 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

8 hours ago -

Editorial: Modi’s Kuwait outreach

8 hours ago -

Telangana HC suspends orders against KCR and Harish Rao

9 hours ago -

Kohli and Smith will be dangerous and hungry: Shastri

9 hours ago