Rewind: Dollar Dominance

The greenback’s hegemony persists because the alternatives fall short and this is not likely to change in the next several decades

By V Thiagarajan

The evolving role of the US dollar in global trade and capital regime has generated a lot of discussion in recent weeks. It’s important to realise that reserve and transaction status is something that, historically, has been gained or lost over a long time horizon. Hence it’s highly unlikely that the world would wake up one day with dollars no longer holding global value. Rather, in examples such as the British pound, there was a multi-decade process by which it went from the centre of world economics to being a second-tier currency.

Also Read

Although the relative importance of the US has declined substantially in the last two decades due to the rise of other blocs, the dollar’s central role is still unaffected. Put briefly, the dollar’s dominance in the financial markets today is much greater than the dominance of the US economy itself. Hence, the discussion of the dollar losing its current role is bereft of any linkage to the reality of international finance and without the understanding of the dollar’s role as the anchor of the rules-based order that governs global economics.

Central banks around the world hold about 59% of their foreign currency reserves in dollars. Much of these reserves are held in US Treasuries

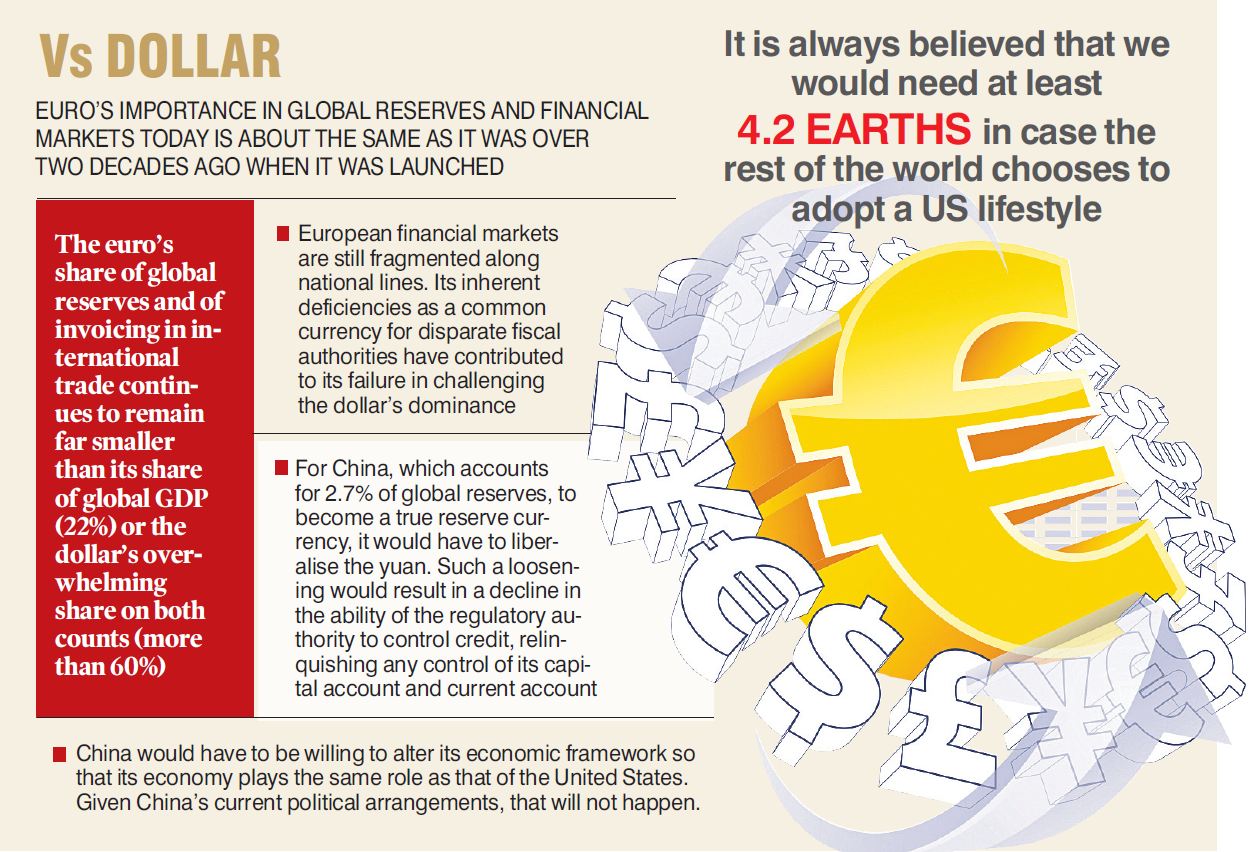

The primacy of the dollar in trade and finance makes it the most attractive currency for countries to hold and, therefore, difficult to supplant. As economist Barry Eichengreen explains in his book Exorbitant Privilege, this is a testament to both the advantages the dollar enjoys as the leading reserve currency and the lack of credible alternatives. The dollar is still the dominant currency for the issuance of bonds, bank loans in foreign currency and the holding of official reserves. The next contender Euro is only challenging the dollar’s position in a limited way with reference to the settlement of international transactions.

World needs Dollar

Since 1980, the US has had a permanent savings deficit, meaning that in absolute terms it is now by far the world’s largest debtor country. But because the dollar is the core of the global financial system, the US has the fortunate side-effect that almost all this debt is priced in US dollars.

The US trade balance—calculated by looking at imports minus exports — is averaging a deficit of nearly $1 trillion per year. That is almost 5% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), at a time when total US debt is already well over 100% of GDP. Such large funding needs help in the easy absorption of global capital that is looking for a place to nest.

It is worth noting that the US consumes far more than it produces — for almost the last 50 years — which implies that the rest of the world has been producing more than they consume. Simply put, the rest of the world has managed to externalise the cost of their weak domestic demand by exporting excess savings to the US and importing their demand which result in massive trade surpluses in these economies. These trade imbalances have only gotten worse in recent times and the US consumption remains the key factor for the rest of the world. It is always believed that we would need at least 4.2 earths in case the rest of the world chooses to adopt a US lifestyle.

About a third of all US debt was held abroad as of 2021, and a little over 60% of the debt issued by non-US companies in a foreign currency was denominated in dollars

Trade surplus generating economies can only accumulate very limited amounts of assets in other advanced economies. As no economy other than the US is big enough to balance more than a tiny share of the world’s accumulated trade surpluses, the dollar continues to stay as the dominant currency.

More importantly, Japan and the EU, along with the most advanced, non-Anglophone economies, run persistent surpluses themselves, so they cannot accommodate the surpluses of countries like China.

It is only because the US and, to a lesser extent, the Anglophone economies, are willing to export unlimited claims on their domestic assets — in the form of stocks, bonds, factories, urban real estate, agricultural property, etc — that the surplus economies of the world are able to implement the mercantilist policies that systematically suppress domestic demand to subsidise their manufacturing competitiveness.

It is about the role the US economy plays in absorbing global savings imbalances. This doesn’t mean that the US must run permanent deficits, as many seem to believe. It just means that it continues to accommodate whatever imbalances the rest of the world creates.

There is an alternative that these surplus-running countries can instead invest their excess savings in the developing world, and while much of the developing world would welcome small persistent capital inflows, the problems with relying on them are fairly obvious. Their economies are far too small to absorb a reasonable share of global excess savings without causing significant domestic dislocations that would make repayment impossibly difficult. In fact, China has — since its ambitious Belt Road Initiative — significantly reduced its already limited exports of capital to developing countries as the risks have become increasingly obvious.

Globally, banks used dollars for approximately 60% of their non-domestic deposits and loans. Adding to this, in the foreign exchange market today, the dollar is on one side of almost 90% of all transactions.

Dollar needs the World

If the dollar gradually loses its place atop the world financial pyramid, what would happen next?

For the US, it would likely mean less access to capital, higher borrowing costs and lower stock market values, among other effects. Having the world’s reserve currency has allowed the US to run large deficits in terms of both international trade and government spending. If foreigners no longer want to hold dollars for savings, it would force significant belt-tightening at home.

The country with the anchor currency enjoys huge benefits. It can finance virtually all its debts to other countries in its own currency. The same applies to imports and exports, which also can largely be paid for in its own currency, as can its investments in other countries.

Federal Reserve estimates that between 1999 and 2019, the dollar accounted for fully 96% of international trade transactions in the Americas, 74% in Asia and 79% around the rest of the globe

In the 1960s, French President De Gaulle referred to this as “America’s exorbitant privilege”. As Barry Eichengreen put it (in 2011): “It costs only a few cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other countries had to pony up $100 of actual goods in order to obtain one.” This led the French to exchange their dollars for gold, whereupon other countries threatened to follow their example. The US accordingly decided to end the link between the dollar and gold in 1971. This effectively marked the end of the Bretton Woods system.

Since almost all large businesses in the world rely on the dollar for their trading and financing, and thus have some ties to the US, those that violate US sanctions run a huge risk. Attempts to replace the SWIFT ((Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) system, which stands behind almost all bank transfers, with a different one will not do the trick as long as the dollar dominates worldwide transactions. By cutting off the ability to transact in dollars, the US can make it difficult for those it blacklists to do business.

Displacing Dollar?

It is possible to imagine a world in which the dollar and the euro stand side by side as the currencies of two large economic regions of equivalent affluence and involvement in world trade. However, it is hard to imagine the euro displacing the dollar as the result of a purely ‘business-driven’ process. It might take a ‘larger than life’ upheaval to dislodge the current equilibrium of dollar dominance.

Since the weights of the world’s largest economies are nowadays more or less the same, it would not be illogical to move to a multi-polar system consisting of the currencies of the major countries. However, as the world is indeed not an optimal currency area, the whole idea of having one global currency is basically flawed. An area qualifies as an optimal currency area only if it has a high level of internal cohesion. In practice, most countries are not naturally optimal currency areas, simply because they are also political entities.

In anticipation of a different standard, governments could actively encourage the use of the SDR (special drawing rights or international reserve asset) by market parties. Countries could issue government and other loans in SDR, private parties could maintain liquidity in this market and central banks could make a start on converting their currency reserves into SDR. This would gradually create the preconditions under which the SDR could possibly develop into a currency anchor over time. It is, however, important that governments do not frustrate this process by forcing the IMF to include other non-convertible currencies in the SDR basket for political reasons. If this happens, the private SDR market will never get off the ground and a global currency system based on the SDR will remain a mirage. Apparently feasible and close at hand, in reality, distant and unachievable.

Cryptocurrencies

Tech evangelists dream of a world where cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin replace government-backed currencies. Such digital currencies are “mined” and transferred via a decentralised network of computers without any issuing authority. Proponents argue that such a system would prevent countries from printing money since the supply of cryptocurrency is limited, much like the gold standard. But this would constrain a government’s policy options during a crisis.

It is always believed that we would need at least 4.2 earths in case the rest of the world chooses to adopt a US lifestyle

From a cursory perspective, the proliferation of bitcoin played into the multipolar narrative, as it provides an outside option to the dollar. In China, mining operators initially took on a nearly mercantilistic role in amassing bitcoin within its borders, but output declined rapidly after it was banned. An economy’s ability to mine bitcoin also rests on its material resources and ability to generate power on a cost-efficient basis— which only raises yet another category in which the US holds primacy.

Additionally, cryptocurrencies have fluctuated wildly in value, reducing their attractiveness. Still, some countries are experimenting with them.

Dollar Standard

Dollar embodies a symbiosis between currency, economy and democracy… or put in academic terms by Martijn and Panitch: a “mutually constitutive relationship between the state and financial markets”.

Stability and the perception of stability are a self-reinforcing cycle, which Norloff has termed the “third face of power” Here, the dollar’s dominance transcends from the empirical to the ideational. Owners of the greenback live in a monetary panopticon, with unrestricted transparency and accessibility.

For the time being, we will live with the current dollar standard with all the consequences that this entails. In any case, it is important that policymakers realise that striving to introduce a euro or a renminbi standard will not solve the underlying problem. It’s hard to compete with the dollar if you don’t have a market analogous to the Treasury market.

Finally, we can grapple with the alternatives to the dollar. Will peripheral fiat alternatives, central bank digital currencies or cryptocurrencies be viable challengers? I believe hegemony persists with the dollar’s incumbency, stability and liquidity, precisely because the alternatives fall short.

Absent a catastrophic US policy error, dollar would remain the most important reserve currency as well as the transaction currency for the next several decades.

Gold Standard

The gold standard, which had its heyday roughly between 1873 and 1914, marks an era that has gone down in history as the first period of globalisation. The important advantage of the gold standard was that there was an objective measure of value (gold) that was recognised by all the participating countries. This was a great benefit, especially for cross-border trade. It is entirely logical that the gold standard marks the first wave of globalisation, which ushered in a flowering of international trade and direct investment.

For domestic payments, however, gold played only a modest role. These were settled mostly in low-value currency. The gold standard was also the wide acceptance of general policy rules. If a country had a foreign trade deficit, this was settled in gold. The gold stocks of the deficit countries declined, while those of the surplus countries increased. If the central banks eased or tightened their domestic money supply in line with the increase or decline in their gold stocks, this ultimately was reflected in domestic purchasing power and therefore their competitive position. This at least was the principle.

One important disadvantage was that the growth of the gold stocks was not sufficient to keep pace with economic growth. This was compensated for in practice because the money supply in the form of demand deposits increased rapidly during the 19th century. This prevented the economy from stalling in deflation due to the money supply being too tight, but it also meant that the amount of gold covering the effective money supply (demand deposits plus notes and coins) had substantially declined over time. The gold standard thus became a so-called gold core standard, meaning that the money supply was only partly covered by gold.

(The author is Chairman of SYFX Treasury Foundation. Views are personal)

- Tags

- globalisation

- US dollar

Related News

-

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

6 hours ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

7 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

7 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

7 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

7 hours ago -

Opinion: The China factor in India-Nepal relations

7 hours ago -

Editorial: Modi’s Kuwait outreach

7 hours ago -

Telangana HC suspends orders against KCR and Harish Rao

8 hours ago