Rewind: Monuments to memory

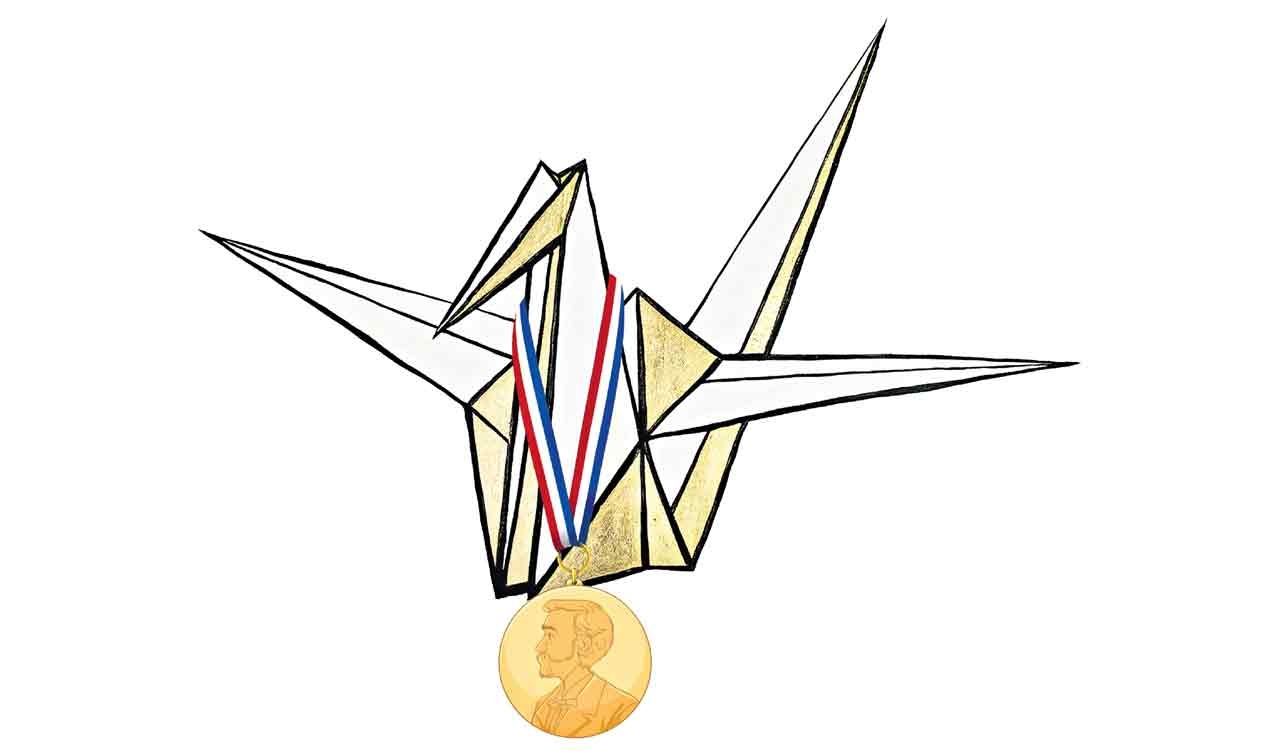

The Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Nihon Hidankyo for its work to denuclearise the world also cited memories of atomic bombs of 1945, and thus revives the debate about memorials

Pramod K Nayar

The Nobel Peace Prize for 2024 to Nihon Hidankyo honoured the victims of the atomic bombings. The Prize announcement stated: ‘One day, the Hibakusha will no longer be among us as witnesses to history. But with a strong culture of remembrance and continued commitment, new generations in Japan are carrying forward the experience and the message of the witnesses’.

As a mnemonic device, as the comparative literature scholar Ann Rigney argues, the literary text is one of the most powerful of monuments. In Japanese literature, we see two specific modes of memorialising Hiroshima-Nagasaki: one which focuses on materiality and the other that seeks to move beyond it.

Before Atomic Literature

The first accounts of the devastation of Hiroshima included both visual and verbal texts, but not Literature. John Hersey’s best-selling Hiroshima (1946) examines the events through the accounts of six survivors. He cites a witness-survivor:

he met hundreds and hundreds who were fleeing, and every one of them seemed to be hurt in some way. The eyebrows of some were burned off and skin hung from their faces and hands. Others, because of pain, held their arms up as if carrying something in both hands … On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns — of undershirt straps and suspenders and, on the skin of some women (since white repelled the heat from the bomb and dark clothes absorbed it and conducted it to the skin), the shapes of flowers they had had on their kimonos.

While there are memorials and monuments, to both tragedy and triumph, Literature, since the time of Pompeii and the letters of Pliny the Younger, remains the preeminent form of monumentalisation

Life magazine’s special report on the bombing, published on 20 August 1945, quoted a Japanese eyewitness account:

All around I found dead and wounded . . . bloated . . . burned with a huge blister . . . all green vegetation perished.

In Wilfred Burchett’s report, ‘The Atomic Plague’ (1945), he wrote:

Of thousands of others, nearer the centre of the explosion, there was no trace. They vanished. The theory in Hiroshima is that the atomic heat was so great that they burned instantly to ashes — except that there were no ashes.

The first sights transformed into memories were often troubled by the fact that the city had disappeared, people had disappeared, and there was not even ash to show they once lived

There was not even ash, notes Burchett (ash is a major presence in 9/11 accounts, most notably in Don DeLillo’s novel, Falling Man).

The question for the first to reach the scene was: how to record the devastation and the yawning absence where a city once was. An early eyewitness cited in Kyoko and Mark Selden’s The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (2015) said:

Hiroshima had disappeared . . . that experience looking down and finding nothing left of Hiroshima was so shocking that I simply can’t express what I felt … Hiroshima didn’t exist — that was mainly what I saw — Hiroshima just didn’t exist.

There was the ethical issue as well: should the photographer capture people in agony? Domon Ken narrates the last few weeks and death of 11-year-old Kenji (a 5-month foetus at the time of the Hiroshima bombing, and had absorbed radiation through his mother) from leukaemia. Ken admits his curiosity about radiation poisoning but also wishes to record it as a sign of evil:

I wished to photograph at least one internal medicine patient who would provide proof of the insidious, persistent character of the “nail marks of the devil.”

Memory Matters

Those who survived were barely human in form: their bodily matter was severely altered. Tōge Sankichi’s speaker in ‘At the Makeshift Aid Station’ looking at the severely burned girls (who no longer have eyes or lips to cry with), wonders if they understand ‘how far transformed from the human they are’. The speaker focuses on the materiality of suffering that gets embedded in his memory.

In Masuji Ibuse’s Black Rain (1969), Shigematsu, the Hiroshima survivor, ponders over the quality of paper and pen to record his experience of an event in which very few materials were left intact. Ibuse by focusing on writing pen and paper materials is calling attention to the fragility of the ecosystem of steel, mortar and brick itself. Shigematsu and his wife, Shigeko, discuss this material act of writing:

“About your journal of the bombing—” she began. “You’re going to present it to the library for posterity, aren’t you? …

“That’s right … It’s my piece of history.”

“Then you ought to take more care over it. Why don’t you write it out with writing-brush ink instead of ordinary pen ink? Writing in pen ink gradually fades away with time, doesn’t it?”

“Don’t be silly. It may fade a little, but not as much as all that.”

Shigeko draws attention to the durability of the memorialising, and then Shigematsu reaches a decision. He decided to rewrite his “Journal of the Bombing” using a brush and Chinese ink… He would have Shigeko copy out again the part already written with a pen, and would himself go on with the rest on Japanese-style writing paper, using a brush.

He had been so thirsty that day. He would have given anything for a drink of water. He had turned a tap by the roadside, and steaming hot water had come out…

Ibuse is speaking here of the materiality of personal memory: remembering the visceral condition of thirst, which years later connects to the act of recording on specific materials.

Immaterial Memories

Symbolism has its own role in memorialising. As we know from the Holocaust, Vietnam, 9/11 and Hiroshima memorials, they become monuments and, as Marita Sturken and others have argued, they constitute a nation’s cultural memory.

Ibuse shifts away from the emphasis on materiality towards the symbolic when he writes

Along the railroad tracks there stretched a long train of refugees like a trail of ants, or like the pilgrims … Seen in the distance, the hill in the park was like nothing so much as a great pale bun with ants swarming all over it.

The symbolism of dehumanisation shows just how insignificant the Japanese were to the Americans.

But how does one speak of memories of material that has disappeared? Tōge Sankichi’s poem ‘The Shadow’ is about the famous photograph from Hiroshima.

Enclosed by a painted fence

on a corner of the bank steps,

stained onto the grain of the dark red stone:

a quiet pattern.

That morning

a flash tens of thousands of degrees hot

burned it all of a sudden onto the thick slab of granite:

Someone’s trunk.

Burned onto the step, cracked and watery red,

the mark of the blood that flowed as intestines melted to mush a shadow

The man had been vaporised by the bomb. The man as matter no longer exists. The shadow, conventionally seen as immaterial, is all that remains. Then of course there is the emphasis on the materiality of the stone on which the shadow is etched. The fact that the whole enterprise now a tourist attraction implies that what matters is how the memories are presented, preserved and marketed. They are at once material and symbolic.

Later authors choose to speak of a different kind of materiality: of toxins embedded into the bodies. In Yoko Tawada’s The Last Children of Tokyo (2018), a post-apocalyptic novel, there is emphasis laid on children who are born with brittle bones. The bomb-marked bodies of humans and non-humans, and the body of the planet (earth and water), come together in Tawada:

While calves drink their mother’s milk, baby birds eat the worms their parents bring them. But worms live in the earth, so when the earth is contaminated, the contamination gets concentrated in the worms.

In some authors, survivors are constituted by their memories of the deaths of others that they witnessed. They move beyond themselves and instead become embodied witnesses to others. In Hara Tamiki’s ‘Summer Flowers’ (1949), Yasuko, herself a survivor, steps outside her own suffering and becomes a witness to another’s, even years later:

Even now Yasuko trembled when she remembered so vividly a neighborhood child she had seen pinned under. It was a child in her own child’s class.

Tamiki implies that survivors in the Japanese context wished to present themselves as unique. Rather: they see themselves as part of a continuum of shared suffering.

There is one more mode through which Hiroshima-Nagasaki’s shared disaster becomes memorialised by the immediate survivors and witnesses. In Tōge Sankichi’s ‘Eyes’, the survivor-speaker describes how he is viewed by other injured survivors:

Eyes fastened to my back, fixed on my shoulder, my arm.

Why do they look at me like this?

He believes these others groan his name when he seeks his family in the ruins. He suspects they stare at him because he looks intact:

Erect, clothed, brow intact and nose undamaged,

I walk on — a human being

Sankichi’s speaker sees himself through the eyes of the many injured.

But authors also record how many survivors did not wish to become memorialised or datafied as part of a national project (studied by Lisa Yoneyama in her book, Hiroshima Traces). Kenzaburo Oe in his Prologue to Hiroshima Notes cites a letter he received from a Hiroshima resident on reading his (Oe’s) essays in the newspaper:

People in Hiroshima prefer to remain silent until they face death. They want to have their own life and death. They do not wish to display their misery for use as ‘data’ in the movement against atomic bombs or in other political struggles.

Clearly opinions are divided even amongst survivors about the politics of memory-making. They do not play the miserable victim card, so to speak, and resist the employment of the hibakusha as a symbol in the anti-nuclear campaigns.

In Keiji Nakazawa’s 10-volume graphic novel, Barefoot Gen (1973-1987), he shows how the Japanese were being used as specimens to study the effects of the bomb, but were not being offered treatment, and the survivor’s son, Koji, resents this:

Specimen? They intend to use her as a specimen in some experiment, like an insect! … The ABCC sees the bomb survivors as nothing more than bugs under a microscope. I bet they’re taking students from your school to serve as guinea pigs too… First they drop the bomb on us and kill our father

And then we let them use our mother as a guinea pig for their experiments.

In Hiromi Kawakami’s short story, ‘God Bless You, 2011’ (a reworking, after Fukushima, of her 1993 tale, ‘God Bless You’), the protagonist, who has gone for a walk, records after returning home:

I recorded my estimate of the radiation I had received that day: thirty micro-sieverts on the surface of my body, and nineteen micro-sieverts of internally received radiation. For the year to date, 2900 micro-sieverts of external radiation, and 1780 micro-sieverts of internal radiation.

The landscape itself, along with the human material body, is a monument. As recently as Fukushima, this form of monumentalisation has been important to the Japanese. In Hideo Furukama’s Fukushima novel, Horses, Horses, in the End the Light Remains Pure (2016), the epithet of the ‘land of the rising sun’ is inverted after the disaster:

Atomic Literature foregrounds the visceral materiality of personal memories of thirst, hunger, and pain, and those who survived the blasts would experience pain for decades so that their bodies are monuments to the events

How does one sing praises to this national land? Especially now, given that there is a second sun in the nuclear core?

The Nobel has reanimated debates around memorialising and the role of the survivor, even as the literary materials around the bombs remain powerful reminders of what happened then. Imagined, re-imagined and reworked, Hiroshima-Nagasaki, and more recently Fukushima, are indelibly material even if marketed or nationalised. Literature etches the shadow of those dematerialised into the monument that is the literary text.

Opinions are divided even amongst survivors about the politics of memory-making. For many Hiroshima-Nagasaki victim-survivors, to be treated as specimens or as living memorials was a double humiliation

Atomic Literature as a monument employs the damaged body as a monument within it. Its job is to trigger the imagination of what it would mean to be bombed in this fashion so that more than just Nihon Hidankyo fight the nuclearisation of the planet.

Such suffering, Denise Levertov reminds us, ‘is not a simulation’.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

1 hour ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

2 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

2 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

2 hours ago -

Opinion: The China factor in India-Nepal relations

3 hours ago -

Editorial: Modi’s Kuwait outreach

3 hours ago -

Telangana HC suspends orders against KCR and Harish Rao

4 hours ago