Rewind: Rendezvous with Rhinos

As we celebrate World Rhino Day, here’s the story of the Indian rhinoceros — of resilience, threatened survival and remarkable conservation efforts

By N Shiva Kumar

The two-man filmmaking team had one aim, to capture close-up footage of a wild pachyderm in its natural habitat. After spotting a large rhinoceros in the grasslands, they carefully inched closer, stepping out of their vehicle and creeping towards the massive creature. The mighty rhinoceros fixed its gaze on them, and tension filled the air as the filmmakers, ignoring a guard’s warnings, edged nearer. The armed guard had repeatedly urged them not to approach the animal closer but the determined cinematographers held their ground, as did the enormous, one-horned beast. In a sudden burst of fury, the rhinoceros charged with a ferocity that left the film crew stunned. Reacting quickly, the guard fired a warning shot into the air, hoping to halt the animal’s advance.

Chaos erupted as the men fled but fate dealt a cruel blow when the guard stumbled and fell on the uneven ground. In a flash, the enraged rhinoceros was upon him, its sharp incisors tearing across his chest, leaving him severely injured. After seven months of recovery and numerous stitches and hitches, the brave guard returned to duty, safeguarding the swarms of tourists visiting Assam’s famed Kaziranga National Park (KNP). Talking to the guard, after he was cured, I was flabbergasted to see his torso, but he had no remorse and said, “after all the rhino was in his domain and we were trespassing.”

Robust body, armoured appearance and characteristic singlehorn make the Indian rhino an unmistakable figure in the wild

My first encounter with a rhinoceros was 27 years ago at Kaziranga. Nevertheless, my second sighting, in Pobitora, a tiny sanctuary also in Assam, home to the highest density of one-horned rhinoceros, was unforgettable. Viewing these magnificent creatures from the back of an elephant, I felt as though I was witnessing a relic from the age of dinosaurs — creatures that defied extinction.

Its robust body, armoured appearance and characteristic single horn make it an unmistakable figure in the wild. But then, since India’s independence in 1947, the story of the Indian rhinoceros has been one of resilience, threatened survival and remarkable conservation efforts. The path toward protecting this species reflects both the challenges and achievements in wildlife conservation in India, yet there is much more to be achieved.

Declining Population

At the time of independence, their population had drastically dwindled due to a combination of factors, including habitat loss, floods, poaching and human-wildlife conflict. Historically, the Indian rhinoceros once roamed across a vast range that extended from the foothills of the Himalayas in northern India and Nepal to northeastern India and the plains of Bhutan.

By the mid-20th century, the rhino population became severely fragmented, confined to the swampy grasslands of Assam and parts of Nepal. Deforestation and the conversion of these fertile lands into agricultural areas pushed the species to the brink. Poaching for the horn, which has immense value in traditional medicine, particularly in China and Southeast Asia, further aggravated the situation.

Early Conservation Efforts

In the years following independence, India faced numerous challenges, including vast economic development and rebuilding the nation. Wildlife conservation was not a top priority in these formative years. However, by the 1950s and 1960s, conservationists began to realise the perilous situation of India’s wildlife, including the rhino. The sprawling Kaziranga National Park became a focal point of these early efforts for its rich biodiversity.

Rhinos are often solitary and their shy behaviour makes it hard to track them consistently, leading to doubtful population counts

Kaziranga was established as a reserve forest in 1905 by Mary Curzon, the wife of then Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, but it wasn’t until 1950 that it officially gained the status of a wildlife sanctuary and graduated to National Park. The protection offered by this sanctuary was limited in scope at the time, with few resources allocated for wildlife protection, but it was a beginning. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, as awareness of conservation issues grew globally, India’s commitment to preserving the rhino strengthened.

Landmark in Conservation

In the late 20th century, political unrest in Assam endangered the rhinoceros, a symbol of regional pride. Though Kaziranga was a sanctuary for rhinos, increased poaching and habitat threats led to conservation concerns. Their population had already dwindled, and by 1983, poaching had claimed over 90 rhinos. This situation distressed former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who, despite local opposition, supported a translocation effort to protect the species. A strong decision to translocate rhinos from Assam to the Dudhwa National Park in Uttar Pradesh took concrete shape. Dudhwa grasslands resembled Assam’s, making it an ideal location. In 1984, five rhinos were airlifted in a specially commissioned Russian cargo plane, accompanied by environmentalists.

Many in Assam feared that relocating rhinos would diminish their cultural significance and weaken the State’s claim to the species. Despite these objections, Indira Gandhi’s support played a pivotal role in this historic conservation effort,ensuring the rhinos’ survival beyond Assam while fostering a national approach to protecting endangered species. This airlift remains a significant moment in both Assam’s political history and India’s conservation movement.

Bold, informed leadership, sensitive to local communities, is crucial for successful conservation. Political backing needs to be sustained over a long period of time as conservation needs constant nurturing for it to succeed and endure in a human-dominated world. The translocation of rhinos from Assam to Dudhwa was exemplary, says Ravi Chellam, CEO, Metastring Foundation, and Coordinator, Biodiversity Collaborative based in Bengaluru.

In 2012, I visited Dudhwa and ventured on an elephant safari to see the viable and thriving population of rhinos. These were from the same stock that was translocated in 1984, nearly 30 years ago from the hinterlands of Assam.

One of the key features of the one-horned rhino’s habitat is its transboundary nature. The rhino’s range extends beyond India into Nepal and Bhutan. Recognising the importance of collaboration, India and Nepal have worked together on various rhino conservation initiatives. Joint anti-poaching efforts and information-sharing between the two countries have been instrumental in reducing cross-border poaching networks.

Rewilding Habitats

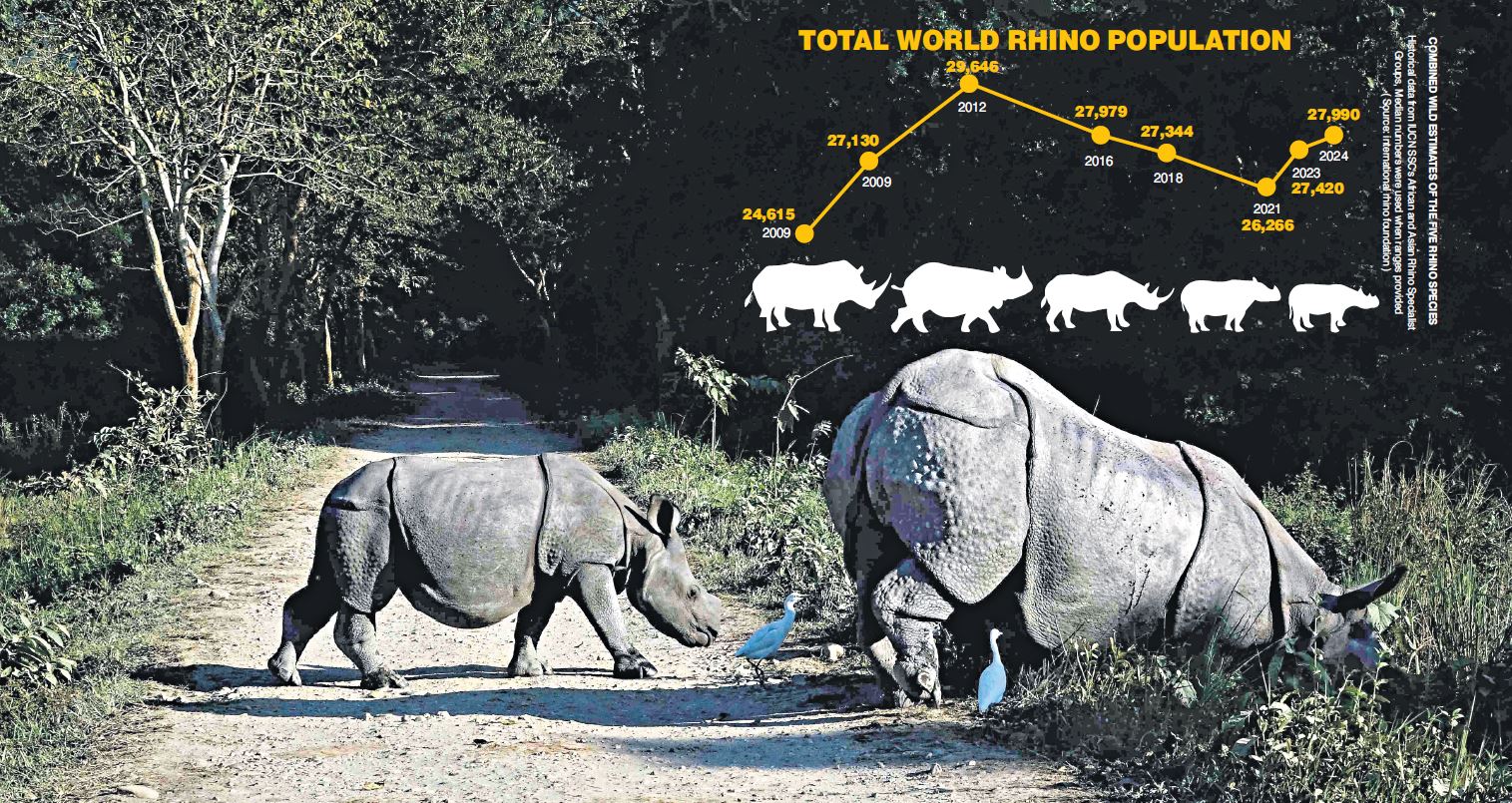

Interestingly, the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) has a word of caution. Logistically, rhino populations in many areas are extremely difficult to count. Rhinos are often solitary and difficult to spot, especially in dense vegetation. Their shy behaviour makes it hard to track them consistently, leading to doubtful population counts. Whether they are roaming over vast landscapes in Africa or navigating through dense jungles in India, surveying these areas is difficult, requiring significant resources such as aerial surveillance, night cameras and tracking teams. Additionally, the animal can disperse over borders between countries, risking either double counting or individuals being missed entirely.

A key feature of one-horned rhino’s habitat is its transboundary nature – its range extends beyond India into Nepal and Bhutan

Governmental wildlife agencies may not have sufficient resources to invest in frequent and comprehensive population assessments. Different countries use various techniques tailored to their species and unique habitats. In India and Nepal, rhinos are counted every 3-4 years by large teams of people riding elephants to spot the animal while staying safe from them and other wildlife. Some use camera traps to identify and estimate rhino populations. And in others, helicopters and aerial teams are used to count them over vast landscapes. No method for counting rhinos is 100% accurate every time, but scientists make their estimates with the best available data.

Conservation Challenges

While there has been remarkable progress in protecting the Indian rhino, conservationists continue to face several challenges. Climate change poses a long-term threat, particularly with increased flooding in Brahmaputra valley, which can destroy their habitats and increase mortality. Additionally, human population growth and expanding agriculture encroach on protected areas, increasing human-wildlife conflict. “The floods are a double-edged sword,” says BC Choudhry, a veteran wildlife consultant and an alumni of Wildlife Institute of India.

“On one hand, they bring life-sustaining silt, rejuvenating the region’s flora and fauna. On the other, the floodwater forces the animal to flee to limited and scattered high grounds stretched over a vast area. It’s often difficult to monitor, exposing the animals to both anthropogenic and natural dangers such as poaching and drowning,” he says.

Future Hopeful

Despite the challenges, the future of the one-horned rhino in India remains hopeful. The success of Project Rhino, the continued growth of the rhino population in Kaziranga, and the re-establishment of rhinos in Dudhwa and Manas National Park (in Assam) are all testament to the resilience of the species and the dedication of conservationists. NGOs, local communities, international conservation organisations and corporate houses have shown an unwavering commitment to the survival of the species.

Wildlife authorities have continuously adapted their strategies to combat the persistent threat of poaching.Today, Kaziranga and other rhino reserves like Pobitora, Orang, Manas, Jaldapara, Gorumara and Dudhwa use modern technology, including drones, GPS and camera traps to detect poaching activities. Additionally, the establishment of fast-response anti-poaching teams has significantly reduced the number of rustling incidents in recent years.

With ongoing efforts, including the expansion of protected areas, stricter anti-poaching measures and habitat restoration, the Indian rhino is on a path to steady recovery.

Kaziranga: A success story

The Kaziranga National Park has boosted its rhino population from a few dozenin the mid-20th century to over 2,500 today. Its success has inspired similar initiatives across India, with community-based tourism providing both conservation funding and local economic benefits. Similar efforts can be seen in other national parks across India. The integration of community-based tourism has further helped provide an economic incentive for the local population to protect the rhino. Wildlife tourism brings much-needed revenue to the region enriching the needy.

(The author is an independent journalist and documentary wildlife photographer)

Related News

-

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

4 hours ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

5 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

5 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

5 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

5 hours ago -

Opinion: The China factor in India-Nepal relations

5 hours ago -

Editorial: Modi’s Kuwait outreach

5 hours ago -

Telangana HC suspends orders against KCR and Harish Rao

6 hours ago