Rewind: The Other Nuked

While Hiroshima-Nagasaki remain the preeminent instances of the nuclear bomb’s devastating effects, there are other nuked elsewhere

By Pramod K Nayar

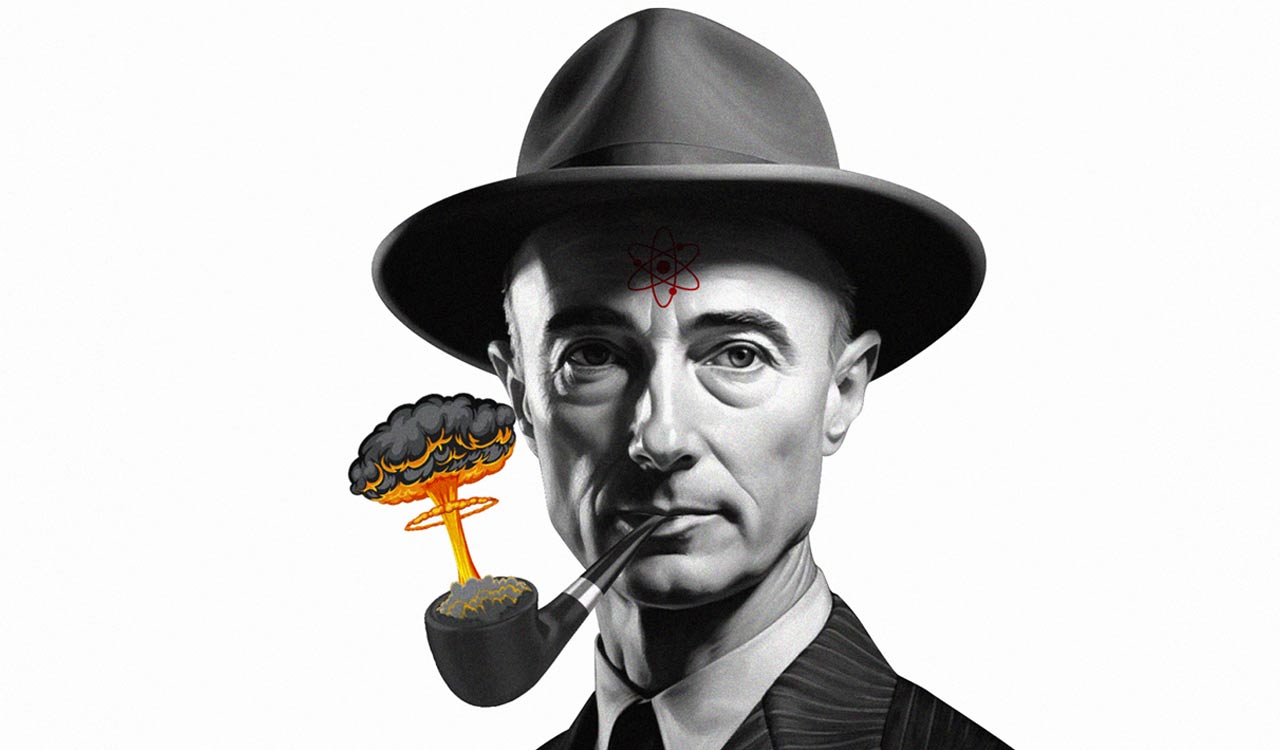

This is Open Season on Oppenheimer. The world, which he helped change with Trinity, remembers Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the most devastating instantiations of the military-scientific complex, every year on the anniversary of the bombings. The anomalies of the bombing — first pointed out by the African American intellectual, WEB Dubois, that the atomic bomb was created to be used on the Germans but was finally deployed against a non-Aryan race, the Japanese, and was hence a ‘race bomb’ — are often forgotten in the commemorative events and collective planetary mourning around Hiroshima-Nagasaki. Attention to the other nuked should not disrupt or dispute the horror of H-N, but 1945 and H-N are not the sole date-place we need to remember.

Also Read

Besides H-N, what needs commemoration is the victim population of the Marshall Islands, the Nevada-Utah region, Maralinga and other places. Trinity set off a chain reaction, in more senses than one.

America’s ‘Doom Towns’

Post Trinity, odd health conditions began to appear in Lincoln and the Sierra counties. The USA was rampaging along the nuclear path and the number of tests increased exponentially. Finding suitable places for the tests was a challenge. Eventually, Utah became the region of choice. The Upshot-Knothole tests of 1953 became notorious because, when the possible consequences of fallout on human population were made aware to the administration, these populations were treated as disposable. In an unbelievable pronouncement, the Atomic Energy Commission’s report justified [the] decision to perform the tests near Utah because the residents were ‘low functioning members of society’, as the report put it.

The atomic bomb, created to be used on a fellow Aryan race, was eventually used on Asian peoples, and was hence a ‘race bomb’, as WEB Dubois noted

These were the ‘downwinders’, those living downwind from the nuclear tests and experiencing, over the next several decades, massive health issues. This is how Utah’s towns became known as ‘doom towns’ — popularised by a graphic novel of the same title by Andrew Kirk and Kristian Purcell.

In the last decade, accounts by people from these regions have been archived, and reveal how America turned on its own populations, dismissed them as disposable people and subjected them to radiation. One such downwinder, Victoria Burgess, writes:

It means we lived downwind from the atomic bombs being tested by the government of our country. As a result of this exposure, our bodies were exposed to lethal radiation at a very young age….at the reunion of my High School Class of ’63, a high percentage of our classmates were suffering with serious illnesses or were dying and we wondered why. By our fortieth class reunion in 2003, one third of our classmates had died from radiation poisoning and various related diseases as a result of the atomic bomb testing.

Burgess sees the parallels with H-N victims:

I find it interesting that the study compares us to the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Japan. Look what we did to those survivors and then we turned around and did it to ourselves. Coincidentally, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed in 1945, the year of my birth!

Sarah Penny, also a Utah downwinder, records how ‘we knew we could die any day from about 5th grade’. She also records her father’s illness:

My father got an upper intestine cancer, which killed him and my mother had continuing health problems, including thyroid problems, which “may” have been caused by the fallout

Here, we see how American citizens and the Japanese are subject to the same forms of decision-making, built on the implicit doctrine of some lives being disposable and non-grievable. Murder and genocide aren’t, as we now know, always about killing people: it is also about letting people die when their deaths could have been prevented.

Entire populations in Utah and Nevada, subject without their knowledge to the fallout from the nuclear tests through the 1940s and ’50s, were the ‘downwinders’, and continue to experience the effects of radiation

Besides the item of apparel, the Bikini Atoll is also known as the site of American nuclear testing through the 1940s and 50s. In the early years of these tests, even the US sailors on the navy ships and personnel on the islands were not fully aware of the true nature of the tests, and were irradiated. These too, then, were ‘downwinders’.

That the US government was not averse to, first, a deliberate concealment of the tests and, secondly, transforming its own citizens into nuked subjects should give us pause to think: if their own citizens were ‘downwinders’ and disposable, would the Japs receive a greater premium on their lives?

The Cloud Mushrooms

The Rongelap of the Pacific and Marshall Islands were also in direct line of the fallout from the series of nuclear tests of the 1940s and 1950s. Jane Dibblin’s Day of Two Suns: US Nuclear Testing and the Pacific Islanders interviews numerous survivors from the region. Dibblin writes:

The exact dose of radiation received by the islanders was never measured, but it was estimated that people on Utrik received 14 rem (140 msv) and those on Rongelap 175 rem (1,750 msv). The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) now recommends that a maximum permissible total body dose to a member of the general public be 0.5 rem a year.

One survivor from Rongelap, Lemoyo Abon, recalls:

After noon, something powdery fell from the sky. Only later were we told it was fallout. With Roko and several cousins, I went to our village on the end of Rongelap island to gather some sprouted coconuts. One cousin climbed the coconut tree and got something in her eyes, so we sent another one up. The same thing happened to her. When we went home – ours was the main village on Rongelap – it was raining. We saw something on the leaves, something yellow. Our parents asked, ‘What’s happened to your hair?’ It looked like we’d rubbed soap powder in it.

That night we couldn’t sleep, our skin itched so much. On our feet were burns, as if from hot water. Our hair fell out.

Only one Aboriginal text, Jessie Lennon’s memoir, I’m the One that Know this Country!, documents the fallout of the Maralinga nuclear tests on her community in Australia’s testing zones. Lennon believes that her cancer came from the tests and, in the tradition of oral history, records: ‘for a long time we’ve been talking Maralinga’.

Perhaps the most famous of such unprecedented fallout is that of the Lucky Dragon, the Japanese fishing trawler that was in the area of the 1 March 1954 Bikini Atoll tests (nicknamed Bravo). Whether the trawler and other ships had been warned off the site is hotly debated, but in any case, when the test occurred, all crew members of the Lucky Dragon were severely exposed to radiation.

The sole document from the incident, Oishi Matashichi’s The Day the Sun Rose in the West: Bikini, the Lucky Dragon, and I states that, instead of being treated as victims, the Jap fishermens were treated as spies. He writes that the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy issued a statement: ‘the Japanese fishermen may have entered the danger zone for a purpose other than fishing and may have spied on the nuclear test’.

Entire regions, then, became laboratories, whether Utah or the Pacific Islands, and everyone was a specimen. The absence of due warnings and subsequent monitoring is underscored by the nuclear scientists themselves. John Clark, involved in the Bikini Atoll tests, records in his memoir:

Nor could we tell beforehand exactly how extensive the air-wave and tidal-wave effects would be or the precise amount and distribution of the “fallout” — the radioactive particles from the nuclear cloud which drop back to earth. In the business of testing nuclear devices there are always a few unknowns.

Sarah Alisabeth Fox writes in her study of the Utah atomic tests, Down Wind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West:

since scientists knew relatively little about the by-products resulting from the tests, the way they traveled through the environment, or their potential effects on humans, many toxic radionuclides were never monitored at all.

The culture of secrecy was integral to nuclear science, and remains so, as Alex Wellerstein has traced in his Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States, and as every single biographer — David Cassidy, Kai Bird-Martin Sherwin, Jeremy Bernstein, etc — of Oppenheimer documents when discussing his problems with the notorious ‘compartmentalization’ of knowledge that Leslie Groves, the military head at Trinity, insisted on.

Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell in Hiroshima in America note the silence of the scientists who built the bomb. They also note that despite the official pressure to not express their views on the political aspects of the bombing, scientists like Leo Szilard did try to have a public discussion around the bombing.

‘No Ordinary Sun’

In one of the most powerful poems ever written on the nuclear bomb, Maori author Hone Tuwhare’s ‘No Ordinary Sun’ (1954) speaks of the nonhuman costs of the technology. The poem, addressed to a tree that has been irradiated, opens with:

Tree let your arms fall:

raise them not sharply in supplication

to the bright enhaloed cloud.

Let your arms lack toughness and

resilience for this is no mere axe

to blunt nor fire to smother.

Tuwhare emphasises that this is not an ordinary fire, and everything that makes the tree a live being will be destroyed:

Your sap shall not rise again

to the moon’s pull.

No more incline a deferential head

to the wind’s talk, or stir

to the tickle of coursing rain

The tree that had survived for centuries, witnessed battles of all sorts, is finally beaten because this sun does not give life, but destroys it:

This is no gallant monsoon’s flash,

no dashing trade wind’s blast.

The fading green of your magic

emanations shall not make pure again

these polluted skies . . . for this

is no ordinary sun.

O tree

in the shadowless mountains

the white plains and

the drab sea floor

your end at last is written.

Farmers from the Utah-Nevada region recorded:

We started noticing white spots coming on [the sheep’s] wool, on the top of their backs. We had a black horse there at camp, and pretty soon he had white spots come on his back and on his rump and all over, from this fallout, I guess.

What needs commemoration is the victim population of the Marshall Islands, Nevada-Utah region, Maralinga and other places. Trinity set off a chain reaction, in more senses than one

Peter Goin photographed an enclosure once used to pen animals and study the impact of the nuclear explosions on them — by intentionally exposing them to radiation from tests. Pine trees — 145 of them — were specially planted at the Nevada test site to monitor the impact of nuclear explosions, and photographs exist that show them swaying under the impact. In his collection of nuclear landscape photographs, Goin notes how in Eneu Island, Bikini Atoll, ‘the residual levels of cesium 137 (half-life of 30 years) absorbed into the coconuts … are still too high for human consumption to be safe’.

After the Chernobyl disaster, cats, dogs and cattle in the area were killed because they had imbibed dangerous levels of radiation. Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, an illustrator for the University of Zurich, collected specimens of insects in areas with nuclear power plants and in regions in direct line of the toxic cloud from Chernobyl (Sweden and Switzerland), and from the Chernobyl region. Her 40-page study ‘Malformation of True Bug (Heteroptera): A Phenotype Field Study on the Possible Influence of Artificial Low-Level Radioactivity’, published in Chemistry & Biodiversity, carried images of the deformed insects from the region. Michael Marder writes in The Chernobyl Herbarium, a collection of images of plants from the Chernobyl region: ‘Strontium-90 accumulates in vascular vegetal tissues, whereas cesium-137 is distributed throughout a plant’.

The culture of secrecy was integral to nuclear science, and remains so. The nuclear sun is ‘no ordinary sun’: it destroys rather than gives life

It is because of this egalitarian nature of nuclear radiation — nothing is immune to it — that, perhaps, the poet William E Stafford makes a nonhuman life form a witness to nuclear tests. In his well-known ‘At the Bomb Testing Site’, a lizard waits in the desert:

At noon in the desert a panting lizard

waited for history, its elbows tense,

watching the curve of a particular road

as if something might happen.

The lizard, says Stafford, ‘was looking at something farther off/than people could see’. Perhaps. it could see beyond what humanity thought and believed Trinity meant (an effort to end the war was the ostensible reason!). All lives are ‘little selves/at the flute end of consequences’ in the larger scheme of such projects. The project, and the land, is indifferent to the events about to occur, or their consequences:

There was just a continent without much on it

under a sky that never cared less.

Ready for a change, the elbows waited.

The hands gripped hard on the desert.

‘Ready for a change’, yes, but a change that is now irreversible. We are all irradiated, the planet forever nuked and the cloud mushrooms over all.

(The author is Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. Also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Hyderabad auto driver foils attempt to kidnap young woman, five held

2 mins ago -

Haiti gang attack on journalists covering hospital reopening leaves 2 dead, several wounded

1 hour ago -

21 dead as Mozambique erupts in violence after election court ruling

2 hours ago -

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

9 hours ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

10 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

10 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

10 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

10 hours ago