India’s fascinating snakes: Biodiversity, encounters, and the vital role of serpents in ecosystems

As Reptile Awareness Day approaches on October 21, let’s dive into the hidden world of these fascinating, yet often misunderstood, animals

By N Shiva Kumar

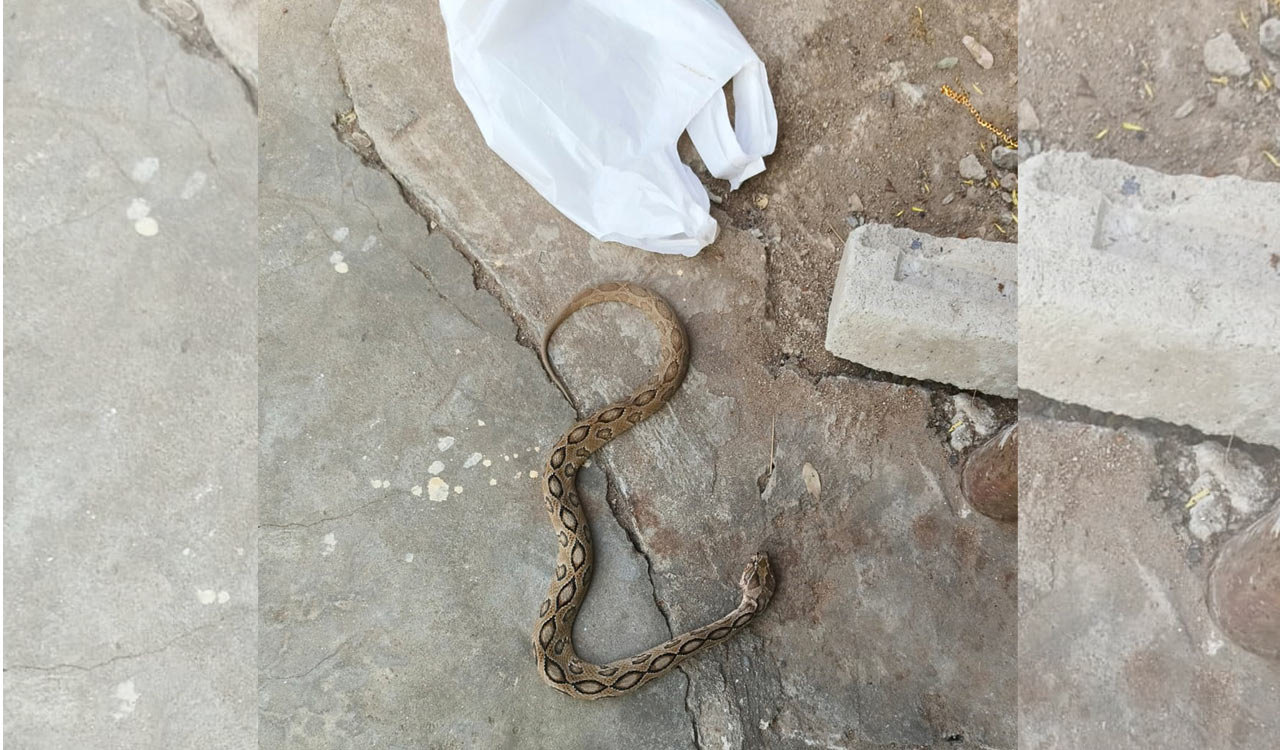

In the first week of October during a jungle drive in Zone-7 of the Ranthambore National Park, a sudden appearance by a spectacular venomous snake turned the safari into a heart-pounding adventure. The snake had slithered into the vehicle, startling the guide and causing the driver to momentarily lose control, leading to a minor mishap. Thankfully, despite the close brush with the deadly Russell’s viper, everyone emerged unscathed. In the same week, another close call occurred when a rider unknowingly travelled 15 km with a saw-scaled viper that had wound up in his motorbike. After months of rain, cooling nights prompt snakes to seek warmth, often sneaking into vehicles—a chilling reminder to stay vigilant!

Also Read

India is a land of contrasts — ancient and contemporary, urban and rural, and teeming with an extraordinary array of wildlife, often crisscrossing the human landscape. Among its lesser-known inhabitants are the reptiles, creatures that often spark fear but are critical to maintaining the ecological balance. From the majestic king-cobra, to monitor lizard, cryptic chameleon to agile geckos, Indian reptiles play vital roles in our ecosystems, acting as both predator and prey.

The vipers are a small snake yet one of the venomous with a potential to inject poison into a human and cause death.

Reptile Diversity

India is home to a staggering variety of reptiles — around 600 species of snakes, lizards, turtles, crocodiles, and more thrive in the people-ridden Indian landscape. This diversity is shaped by the country’s varied terrains, from dense rainforests and arid deserts to sprawling mangroves and alpine ecosystems. Each habitat has its own specialised reptilian residents. For instance, the Indian rock python slithers silently through the wetlands and forests, while the desert-dwelling spiny-tailed lizard thrives in the extreme heat of Rajasthan. These reptiles have evolved remarkable adaptations to survive in their unique environments, making India a haven for herpetologists and nature enthusiasts alike.

With this remarkable diversity of reptiles, including around 300 species of snakes, our country also hosts over 200 species of lizards, with geckos and skinks being the most commonly found. Additionally, there are about 36 species of turtles and tortoises, covering both freshwater and marine varieties. Among crocodiles, India has three species—the mugger and saltwater crocodiles, and the unique gharial—each adding to the country’s rich reptilian biodiversity.

Coiled in Crisis

As the reptilian world is a vast subject to dwell upon, let’s turn our attention predominantly to the scaly, slithering sentinels of India’s wilderness — snakes, coiled creatures that are both misunderstood and fighting for survival. Paradoxically, snakes have been both revered and feared throughout history. Worshipped in temples, even adored by yesteryear kings across the country, they are symbols of divinity for some, yet many fear them so intensely that they’re killed on sight.

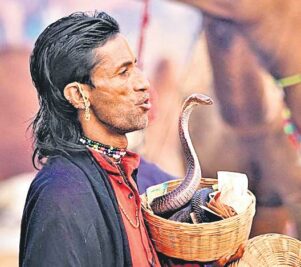

India’s reputation as the land of snake charmers before independence is well-known globally. The image of a charmer playing his flute while a snake sways to the tune is deeply ingrained in cultural lore, along with the famous Indian rope trick. However, the enactment of the Wildlife (Protection) Act in 1972 brought an end to this ancient practice. Since then, snake charmers have gradually faded from urban landscapes, their role taken over by wildlife NGOs and professional snake catchers who are trained to tackle snakes. Being coldblooded creatures’ snakes, particularly in the rainy seasons, seek solace in towns and cities where they find food easily in the form of rats and rodents that thrive because of human-created trash.

As cities, towns, and villages expanded erratically, human encroachment into the snakes’ natural habitats escalated, leading to more frequent human-snake conflicts. Today, the challenge is not only to protect people from snakes but also to safeguard these misunderstood creatures from human aggression. The fate of snakes in India’s evolving landscape remains in precarious balance and needs to be addressed judiciously as the economy is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the environment.

My love for reptiles started during my college days when I won the 2nd prize in a photography competition held by the state forest department in 1981 and the award was a 200-page ‘Common Indian Snakes — a field guide by Romulus Whitaker.’ A year later, I was fortunate to see the King Cobra, the largest poisonous snake in India, brought injured to Hyderabad Zoo for treatment from Salur, 50km north of Araku Valley on the Andhra and Orissa border. Another encounter was with a massive 12-foot python in Tadoba National Park while exploring the jungles. Later, I was surprised by a green vine snake, staring at me from a shrub during a heritage walk around Bidar monuments also in the 1980s. My saga of snake love continues, albeit sporadically, with happenstances with sand boas, rat snakes, vipers, keelbacks, banded kukri, flying snakes, cobras etc as I wander across the last remains of original jungles.

Serpentine Wonders

Of all the reptiles in India, none are more iconic and toxic than snakes. India’s serpents are renowned both for their beauty and their bite, with some species being among the deadliest in the world. Yet, for all the fear they invoke, snakes are vital components of ecosystems, controlling populations of pests and serving as prey for larger animals. About 17% of snakes in India are venomous, and of those, only about 7% are capable of killing a human. Obviously, snakes have venom to kill prey as a meal, not humans. “Unfortunately, it is difficult to estimate the population of snakes due to their cryptic nature and sadly three species of snakes are reported critically endangered due to man’s folly,” says Chetan Rao, a herpetologist.

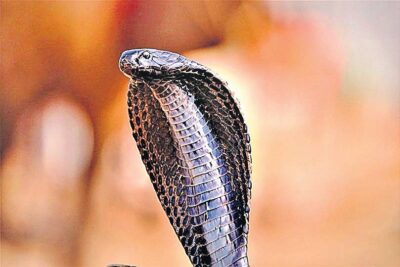

Cobra is another venomous snake that is highly worshipped and

at the same time hated across India.

A snakebite isn’t always as deadly as it seems. “Even a venomous snake may not inject enough venom to cause harm, especially if it has recently had a meal. Such bites, known as ‘dry bites,’ can leave victims more shaken by fear than poison. Often, the real danger comes from panic and anxiety that set in, rather than the bite itself. Regrettably, most people can’t tell the difference between venomous and non-venomous snakes, leading to unnecessary terror. In rural areas, many bites occur simply because people unknowingly step on snakes while walking barefoot, particularly during the monsoon season when snakes are more active. However, with simple precautions like wearing protective footwear and staying alert, many snakebites can be prevented. Fear is often more lethal than the bite itself,” explains Dr BC Choudhry, a wildlife consultant with over 40 years of experience in India’s wilderness.

In 1899, about 125 years ago, plague ravaged Bombay, WaldemarHaffkine, a Russian bacteriologist, set up a small lab that would become the Haffkine Institute. Initially focused on developing vaccines, the institute quickly expanded its research. In the early 20th century, snakebites posed a significant threat across India mostly in the rural areas. Haffkine team turned their attention to snake venom, creating life-saving antivenoms. With painstaking experiments on local serpents like cobras and vipers, they pioneered venom research in India. The institute became a beacon of hope, revolutionising public health and cementing its place as a leader in antivenom science, saving countless lives to this day.

The Madras Snake Park, in Chennai, is a perfect sanctuary for India’s misunderstood reptiles. Founded in 1972 by renowned herpetologist Romulus Whitaker, it plays a crucial role in snake conservation and education. The park’s mission goes beyond display; it rescues, rehabilitates, and spreads awareness about the ecological importance of snakes. Through research, breeding programmes and community outreach, the park dispels myths, teaching people to coexist with these vital creatures, ensuring their survival in the wild. The Irulas, an indigenous community in Tamil Nadu known for their snake-catching skills and knowledge of serpents, have been sensibly deployed in the snake park. The park remains a beacon of reptile conservation in India.

Reptiles in Ecosystems

Snake charmers, now a vanishing tribe, keep snakes as pets and make a living out of them. Cobra is another venomous snake that is highly worshipped and

Reptiles have long held a place in India’s cultural and spiritual landscape. Snakes, in particular, are revered and feared in equal measure. The cobra is associated with the Hindu gods, and snake festivals like Nag Panchami celebrate these reptiles, offering a unique blend of reverence and fear. Ecologically, reptiles are indispensable. They control populations of pests like rats, rodents and insects, which helps prevent the spread of diseases and maintain crop health. In turn, reptiles serve as prey for birds of prey, larger mammals, and even humans in some regions, making them a key link in the food web. Their roles as predators and prey maintain the delicate balance of ecosystems, particularly in forest, grassland and wetland habitats.

So the next time you see a snake don’t jump to conclusions that they are dangerous or chasing you or ready to bite you, instead just watch the legless creature move with remarkable agility. By using strong muscles along their long, flexible bodies they can navigate any surface with ease as their scales grip surfaces, allowing them to slither smoothly with stealth. Snakes are one of the most successful groups of vertebrates, with over 3,000 species reported around the globe.

Hiss…..

- About 17% of snakes in India are venomous, and of those, only about 7% are capable of killing a human

- King Cobra, the world’s longest venomous snake, can grow up to 18 feet and is known for its unique diet of other snakes. Found across India, this intelligent predator symbolises power in many cultures, often displaying curiosity and problem-solving skills while hunting.

- Russell’s Viper, a venomous snake of grasslands, is known for its loud hiss and is responsible for many snakebite deaths. Despite its danger, it helps control rodent populations, especially in agricultural areas.

- The Indian Rock Python, a non-venomous constrictor, relies on strength to subdue prey. Though massive, it avoids humans and plays a vital role in maintaining ecosystem balance by preventing mammal overpopulation

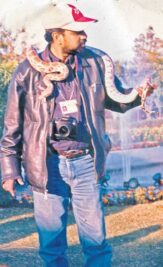

The author with a python around his neck at a courtyard of a hotel on the Delhi-Agra highway in the 1990s when

snake charmers still practised their profession

(The author is an independent journalist and documentary wildlife photographer)

Related News

-

Ethiopian wolves’ taste for nectar! Is Africa’s most endangered carnivore a pollinator?

-

Kothagudem: Man kills Russell’s viper after bite, rushes to SCCL hospital with snake for treatment

-

How do pollinators get attracted to flowers?

-

Traffic advisory: Gachibowli flyover closed from 11 PM to 6 AM on Oct 22 and 28

-

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

2 hours ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

3 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

3 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

3 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

3 hours ago -

Opinion: The China factor in India-Nepal relations

4 hours ago -

Editorial: Modi’s Kuwait outreach

4 hours ago -

Telangana HC suspends orders against KCR and Harish Rao

4 hours ago